Posted on 25th January 2026 by Prof. David Hughes & Miguel Flavian

The blog is back, returning to one of the hottest (and most enthusiastically argued-over) topics in the UK food and farming debate of the moment. We do recognise that many readers are busy, impatient and have a predilection to consume information via the phone whilst undertaking other tasks. As a result, we offer you: Option 1 – the “are you sitting comfortably with a bottle of wine?” version ; or Option 2 – “the cup of coffee and in a hurry” version. The latter is thanks to the summarising skills of ChatGPT and is waiting patiently for you at the end of the post.

The Bottle of Wine Version

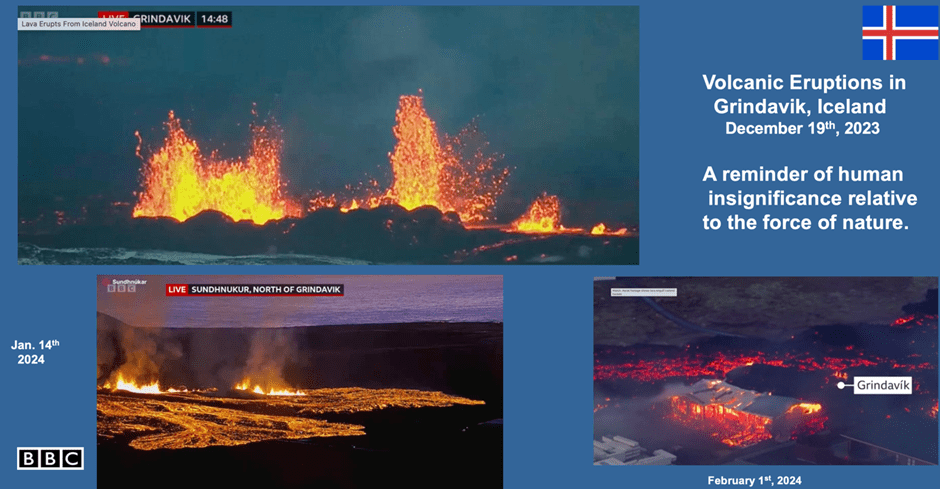

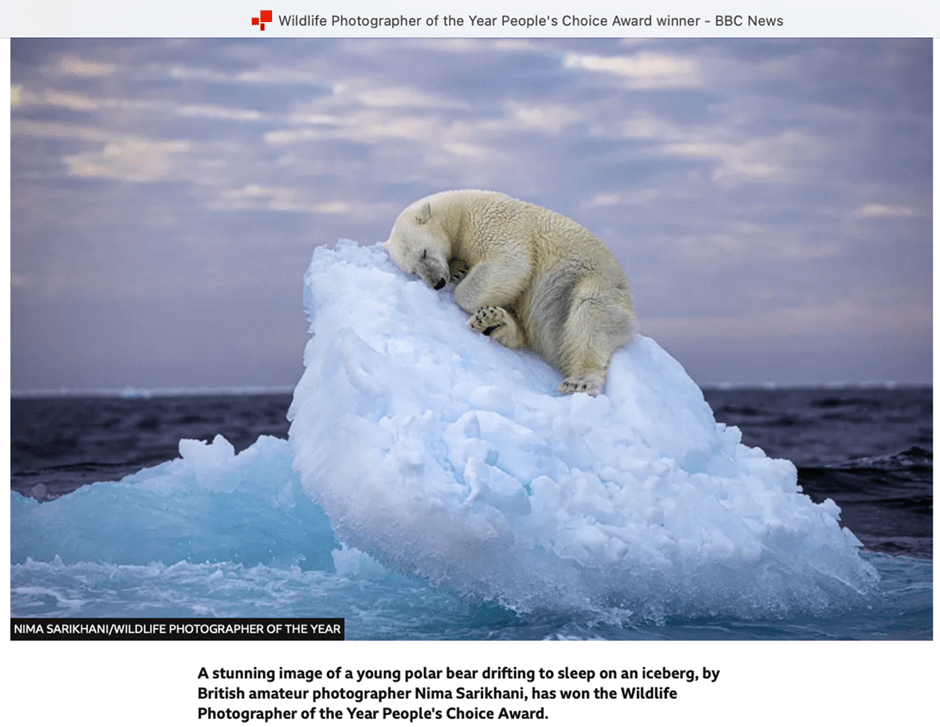

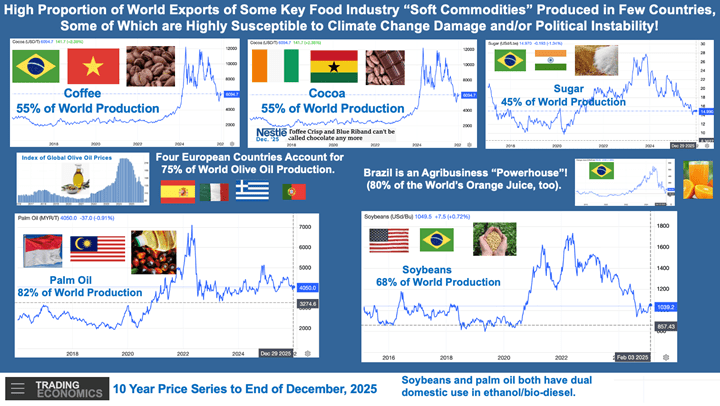

In December 2025, the FAO Global Food Price Index was 2% lower than a year earlier, hurrah! But, what’s vexing consumers is that global food prices are 31% higher than pre-Covid and most household incomes haven’t seen a similar rise. Good news for farmers? No, across the world many farmers are incandescent with rage as they’re buffeted by inflationary spikes in input costs, Trumpian tariff excesses, margin squeezes from more powerful supply chain “partners”, and extreme climate events. Concerns about national food security have bubbled to the top of the political agenda and are rife in the media with dark talk about the prospect of empty supermarket shelves for key foods.

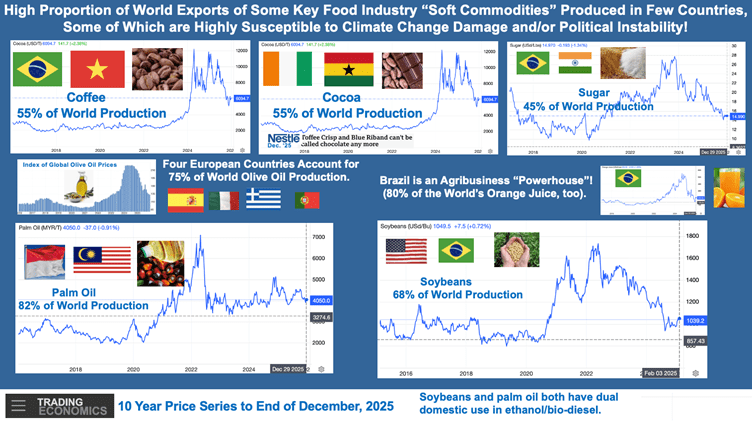

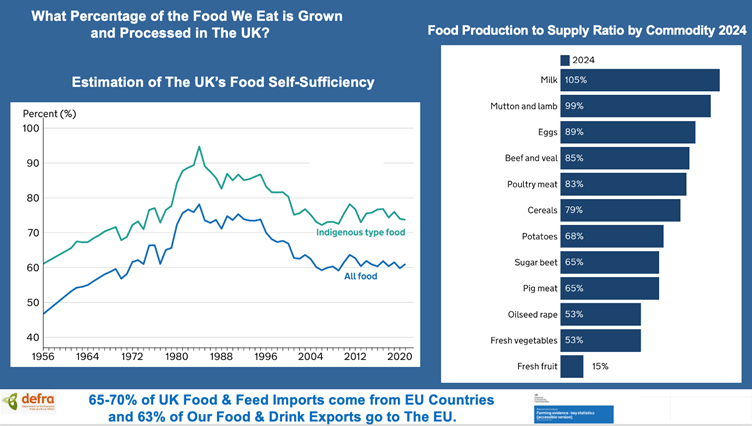

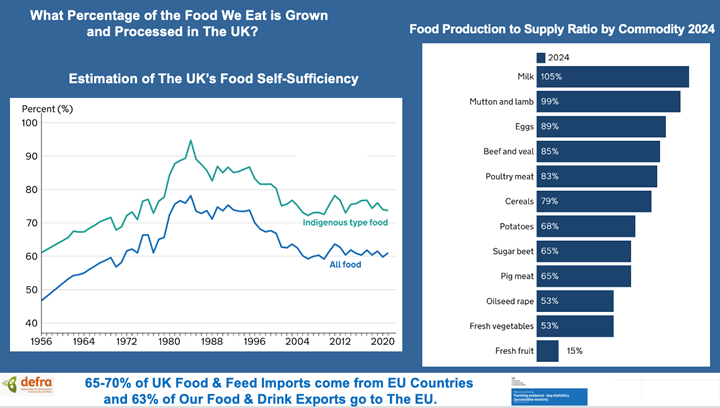

A high proportion of world exports of key food industry “soft commodities” are produced in few countries: e.g. coffee, cocoa, sugar, palm oil, olive oil, orange juice. If they have production problems, we have grocery procurement problems! At home and in history, UK food production was a shared job between our farmers and those offshore, largely from “The British Commonwealth”. UK food self-sufficiency was below 50% pre-WW2, rising to 75+% in our earlier EU years in the 1980’s, then, drifted down to settle around 60% in the 2000’s. In her Farming Profitability Review (December 2025), Minette Batters sees one of the routes to improve profitability of British farming and to increase our food self-sufficiency is through growing the British food & drink brand at home and abroad by “growing, making, producing and selling more from our farms….”. Food production expansion may be a key element in our national farming and food strategy but begs the question why are we only 60% self-sufficient in food now? Each of the principal commodity areas have their own explanatory tales:

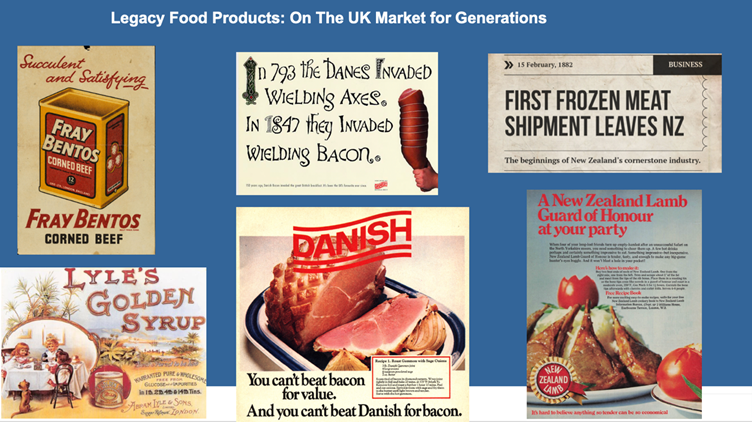

- milk and mutton & lamb – these were shared production duties with New Zealand, whereas beef in early years was principally British and supplemented by Argentina and Uruguay (remember cans of corned beef? Fray Bentos is a city in Uruguay!). Latterly, Irish beef has been commonplace in our market. What’s surprising is that the UK, uncommonly good at growing grass, didn’t emerge as a significant milk product and red meat exporter;

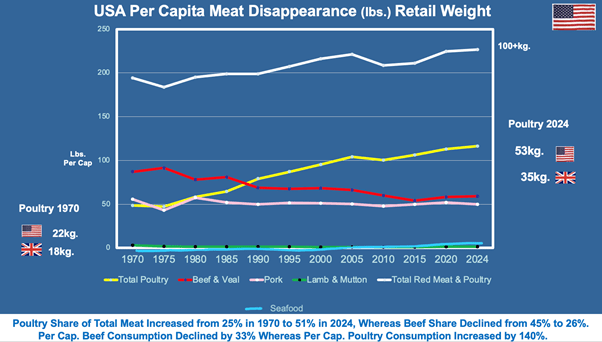

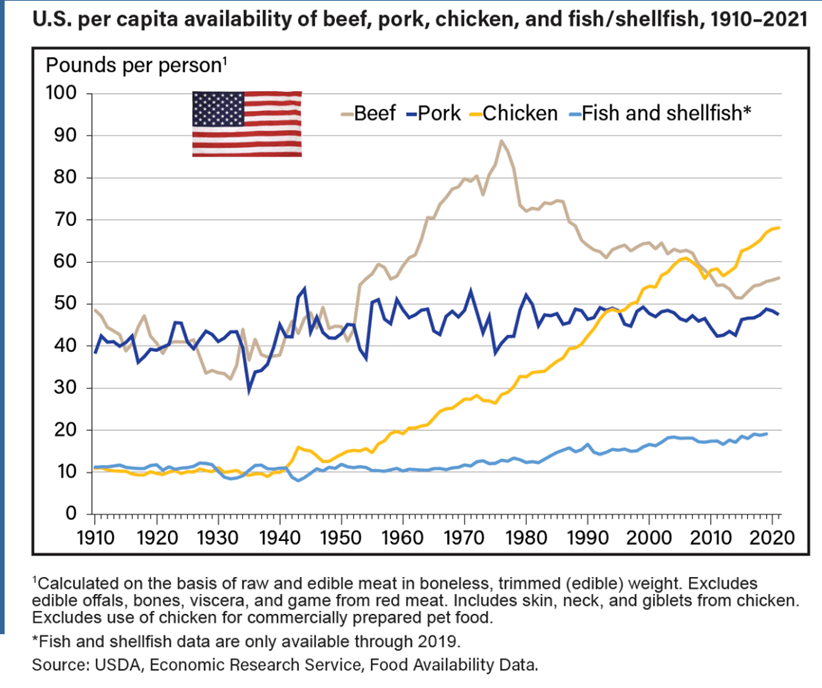

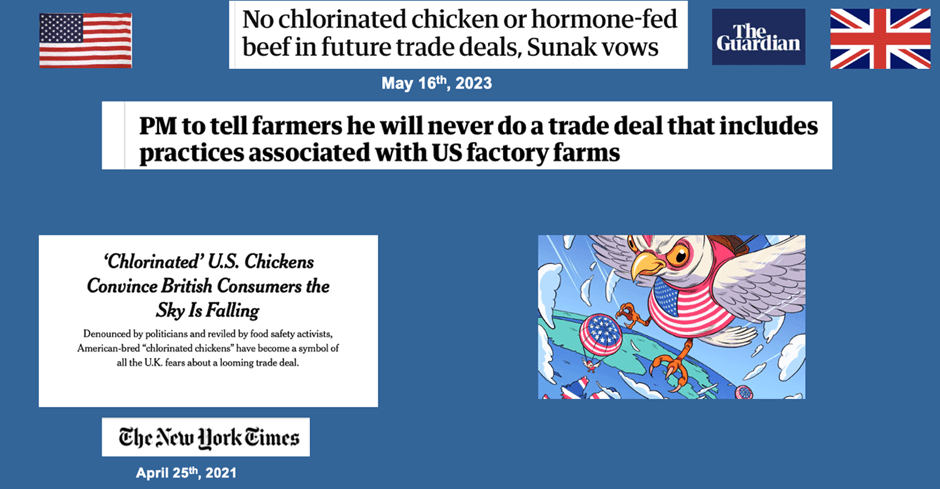

- we’re good at poultry but, also, significant importers of chicken. Don’t look at the supermarket meat aisles for chilled imported chicken because that’s where the UK product is located. Most of the imported chicken, from inter alia Thailand, Poland, Ukraine, China, emerges in our market as the raw material for nuggets and kebabs sold, not least, via food service – “fast” chicken the default takeaway!;

- sugar was a shared job with our Caribbean family and now, like oilseed rape, both these commodities have “neonic” pesticide issues constraining increases in home production;

- our “low level” of sufficiency in potatoes, in part, is explained by the inexorable consumer shift to processed potato products (particularly French fries). Our import source are two small neighbours The Netherlands and Belgium who account for half the 10 million tonnes of processed potatoes exported globally. Why we’re not with them and could we be partnering global exporters as they run out of land at home for spuds are pertinent questions;

- UK produced pig meat is at similar modest levels as potatoes. Most pork in the UK is consumed in processed form – retail sales of sausages and bacon are 3 times that of fresh pork. In history, Denmark dominated our bacon market and, from the very early 1900s we were reminded in their advertisements that “Good bacon has DANISH written all over it”!;

- our lowest self-sufficiency is for vegetables and particularly fruit. The EU is the principal source for veg. and we scour the world for fresh fruit. Arguably, global warming may advantage domestic production of fruit, although traditional favourites apples & pears have struggled to compete with more fashionable fruit in our own domestic market;

- cereal self-sufficiency has drifted lower since the hay days of EU membership but, at 79%, is well above the levels of the pre-1970s when Canadian wheat was principally used to make our bread. “Climate events” at home and abroad and global trade turmoil have brought increasing instability in domestic yields (and, thus, returns) and global supply.

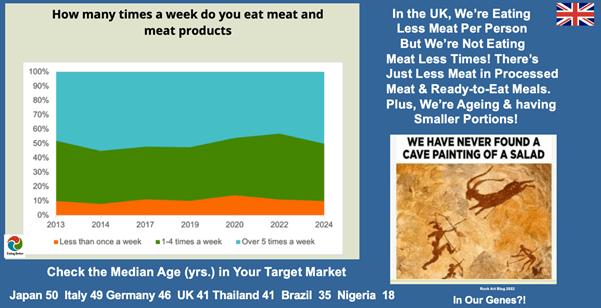

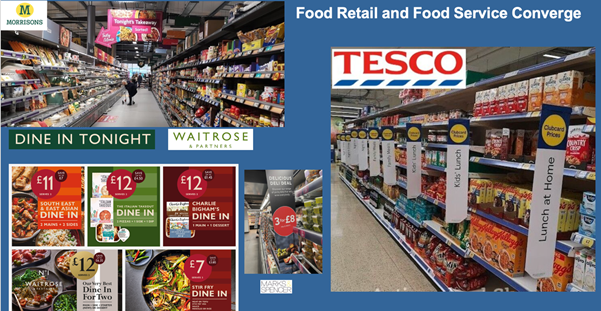

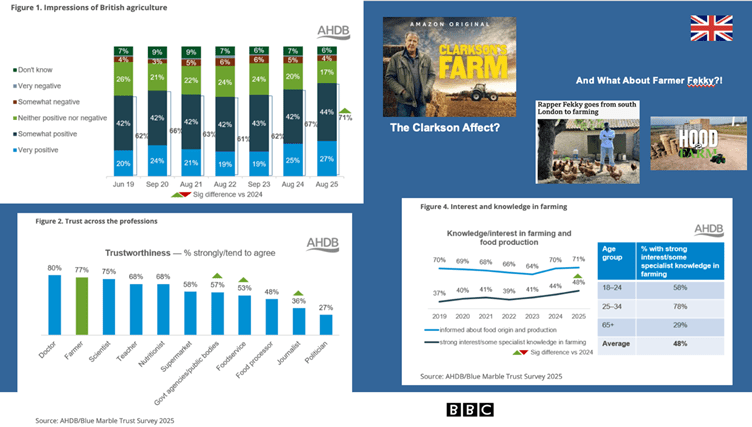

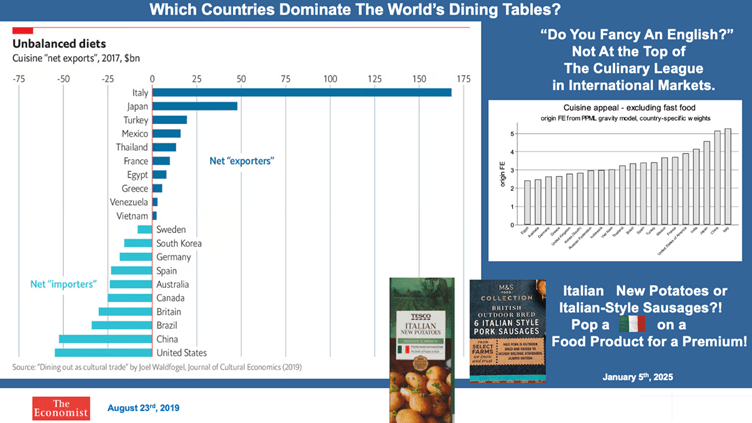

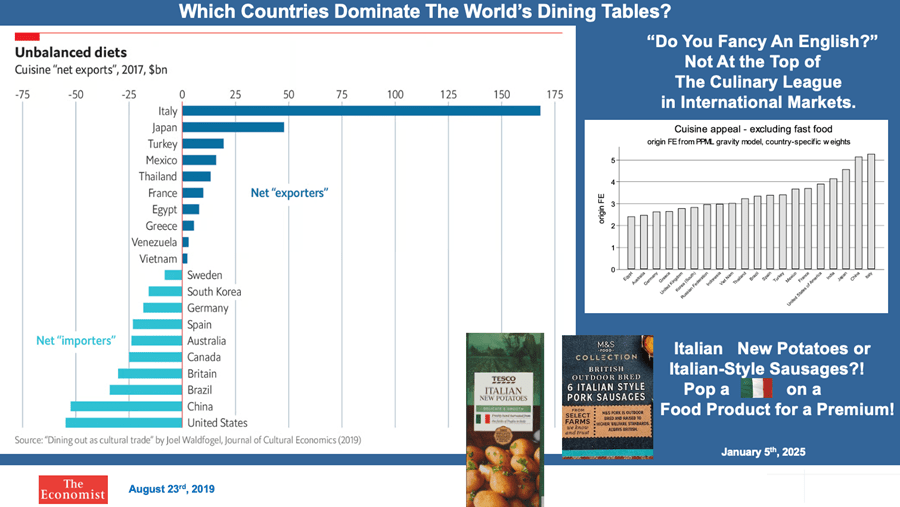

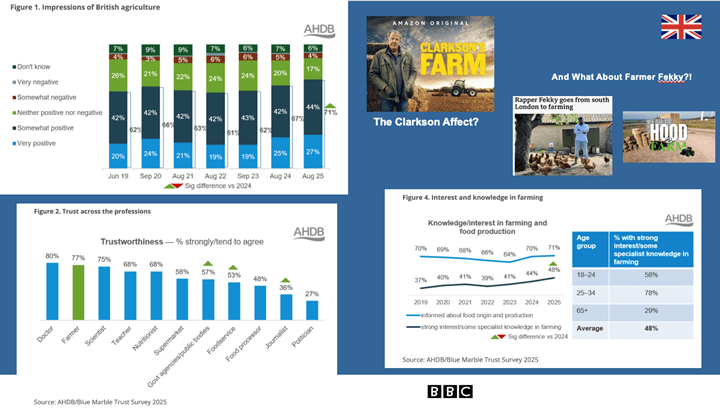

Returning to the mission “to grow the British brand for food & drink”, let’s start in our best market, i.e. The UK. Our consumers have a positive impression of British agriculture and accord farmers with a high level of trust. Interest in farming and food production is increasing, particularly amongst younger consumers (a Clarkson affect?). However, whilst they’re positive about British food, they also like imported foods. Why shouldn’t they as it’s been in our market for centuries. Preference for “my own country’s food” is highest in Italy – arguably, the country with the strongest food culture in The World. Italian cuisine, too, has pride of place on the dining tables of countries across the world, ahead of Chinese, Japanese and Indian meals. Tourists traversing the globe are unlikely to ask “anybody fancy an English?” when deciding what meal to eat of an evening! In UK supermarkets, food retail and food service is converging – shoppers are more likely to buy a meal than a collection of ingredients – and the meal can be selected from a panoply of international cuisines. The retail ready meals market, at £5.3bn. in 2025, was substantially larger than the combined retail sale of chilled beef, pork and lamb cuts. On ready meals, the UK is no global outlier. Buying the cooked meal from a market is common in Asia (e.g. Thailand) but there the meal is very likely to be traditional, local fare. Within our own market, a mention of Italy or France in relation to food, often as not, is associated with a premium priced product.

Buying a ready-to-eat snack/mini meal or full meal rather than the ingredients to make them presents a further challenge for our farmers as it places them one step back from the consumer by placing a food processor in between. If it’s a special snack/meal we may take the time to investigate the food story and explore provenance but if the meal is on the run, then, convenience of purchase and immediate consumption are the key drivers. Do you know anybody who has asked the doner kebab vendor “is the chicken free range?”! The consumer’s definition of convenience has been in flux for generations. For Gen. Z (30 years and under), convenient means NOW!

Across the globe, there’s a distinct trend towards international cuisines, in pure or hybrid/commingled form, particularly demanded by younger consumers (under-45s – Gen. Z & Millennials). Knowledge of and interest in “foreign foods” has been accelerated by social media. The rise of Korean food in the UK is a case in point – Korean pop culture spawned interest in other things Korean, including its iconic gut-healthy kimchi! Instagram and TikTok have been hugely influential in accelerating international food trends, with a quintessential example being the Canadian TikToker who, in 2024, generated a veritable tsunami of interest in Asian cucumber salads, and in the UK, 3 years earlier, Little Moon’s Japanese-inspired mochi (r)ice cream balls rocketed their way to retail success via TikTok.

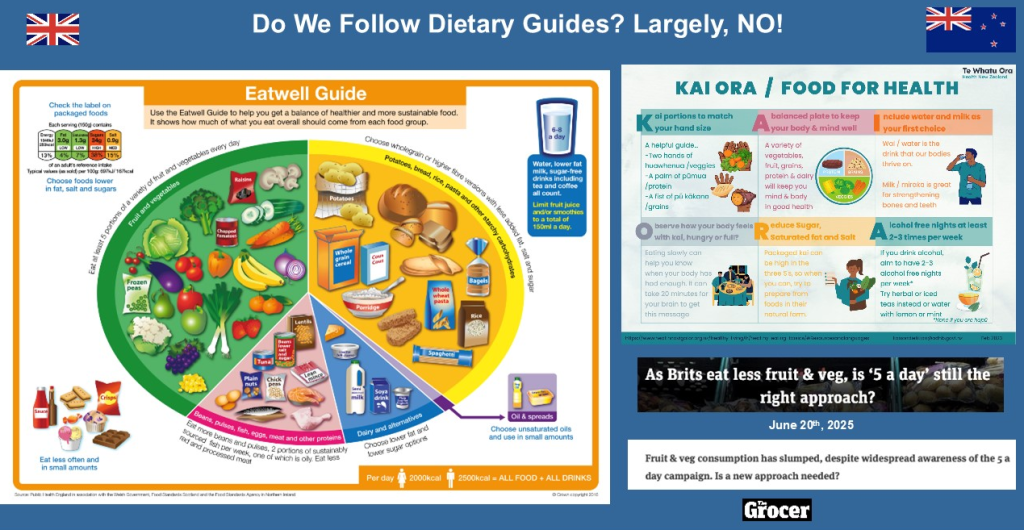

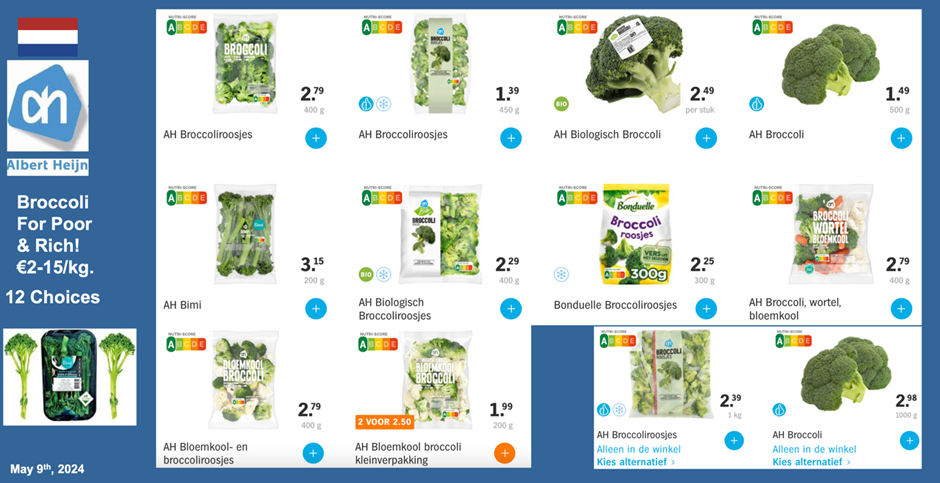

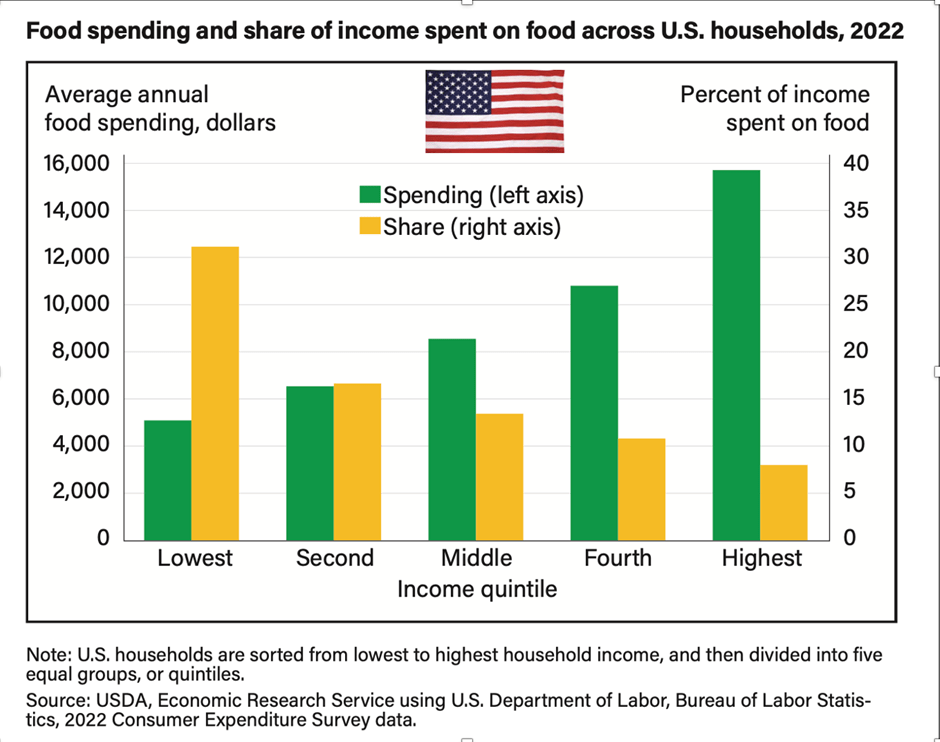

What of the UK food consumer in 2026? British consumers have the lowest retail food prices in Western Europe (the UK grocery sector is the most competitive in the known world) but living costs are amongst the highest (bar Denmark and Ireland). Half of our households are struggling financially and seek to fill family tummies tastily but cheaply. Of course, family health is important and supporting home food producers but “needs must” and cost per calorie prevail making it challenging to pay a premium for local high standard environmental and animal welfare food.

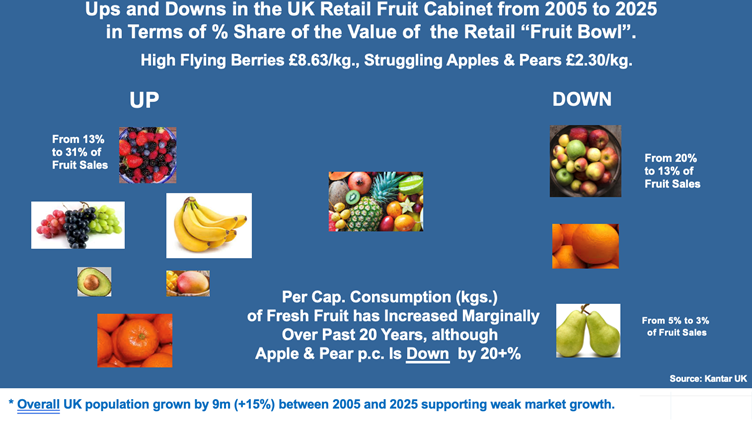

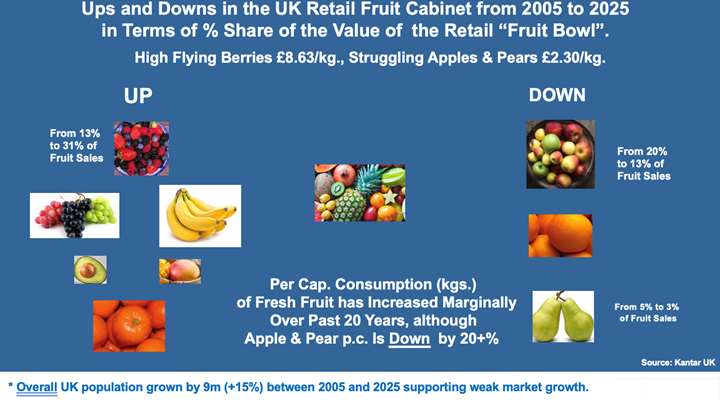

So, when shoppers are in the supermarket is it only about low price? Look at the ups and downs in the UK retail fresh fruit cabinet over the past 20 years. Keep in mind that for fresh fruit UK self-sufficiency (15%) is the lowest of any food category:

- per capita fresh fruit consumption has increased over the 20-year period but only marginally.

- the highflying fruit include imported easy peeler citrus, grapes, bananas, avocados, tropical fruits and fresh berries from home and abroad. The strugglers include oranges and traditional favourites apples & pears;

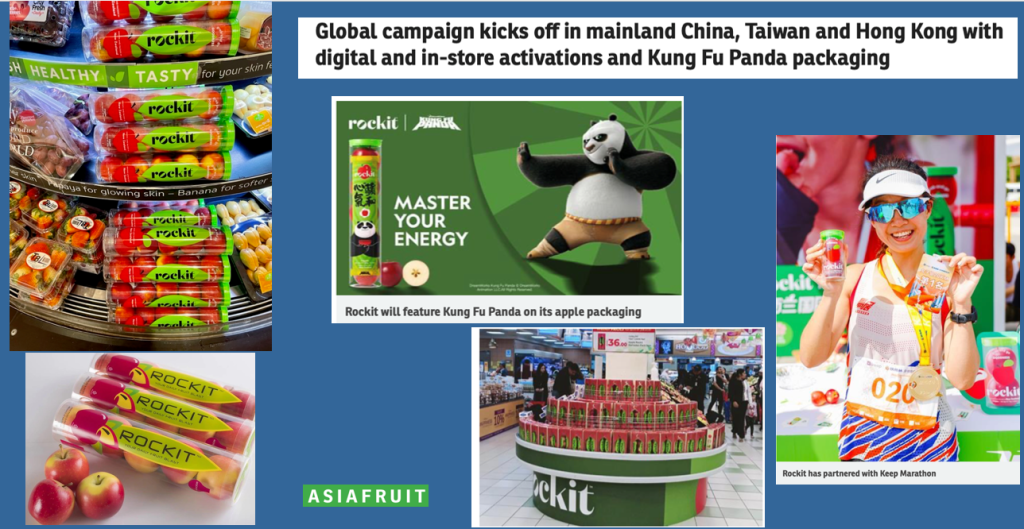

- relatively high-priced berries (av. £8.63/kg.) have zoomed ahead of apples & pears (£2.30/kg.) jumping from 13% to 31% of retail fruit sales, whereas apples have declined from 20% to 13% and pears 5% to 3%. Clearly, in the mind’s eye of the shopper when choosing fruit, price is not the be all and end all!

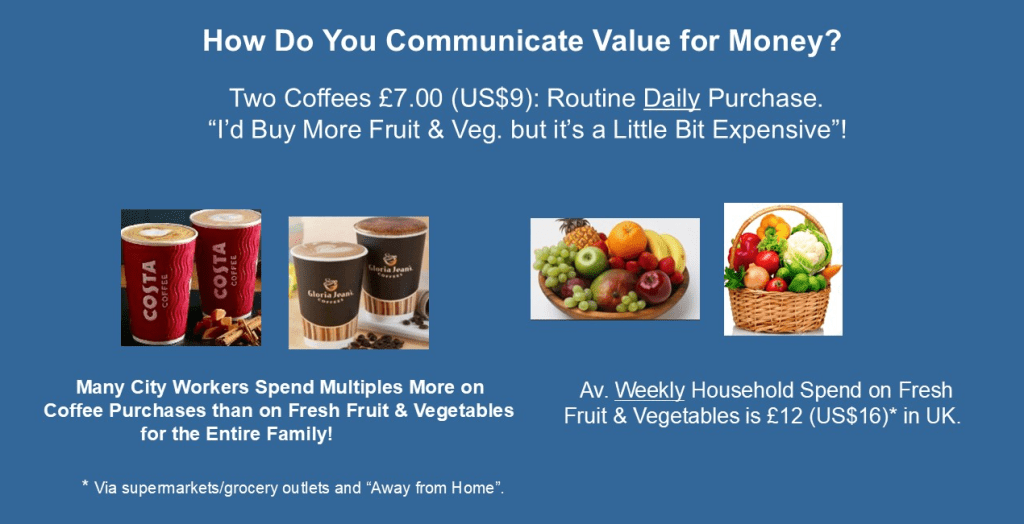

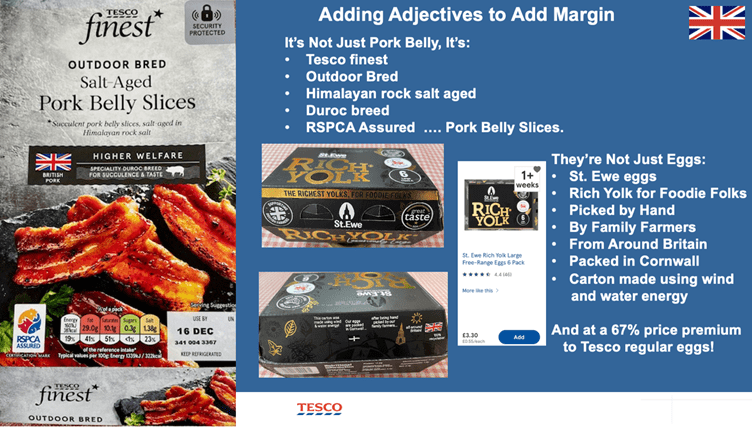

Average weekly spend per UK household on fresh fruit is £12. Routinely, many city workers spend double or more than that on buying cups of coffee. Yet, in market research surveys, a common response when rationalising their modest fruit and veg. purchases is “I’d buy more but they’re a bit expensive”! If we want British shoppers to buy more home-produced food, then, we’ll have to up our efforts to communicate that it’s better value for money than the competition. Think back to the classic 1971 L’Oréal Paris beauty product strapline “because I’m Worth It!”. Amended, it works well for British food & drink: “Because We’re Worth It!”, the We being the consumer and family, the producer, society and the environment. We need to “de-commoditise” the British offer relative to imports. Tell the story and add adjectives because they add margin to all in the supply chain. Concomitantly, there’s a requirement that regulations ensure that imported food products match the standards required of domestic producers. Otherwise, the locals are on a hiding to nothing!

Expanding our food export opportunities will be principally focussed on premium overseas markets and the closer the better – 62% of current food exports go to the EU and 76% of our food imports come from there. They know us and we know them! The importance of introducing the proposed SPS (Sanitary and Phyto-Sanitary) Agreement to reduce import/export costs is commonsensical. Outside of the EU, particularly for premium cheese, the USA and high-income segments of Asian markets have exciting potential. But we won’t be swashbuckling our way across international food commodity markets, however, as we’re not low-cost producers relative to the agribusiness behemoths such as Brasil and USA. Further, like many industries, the agribusiness and food business world is polarising – the big are getting bigger. For instance:

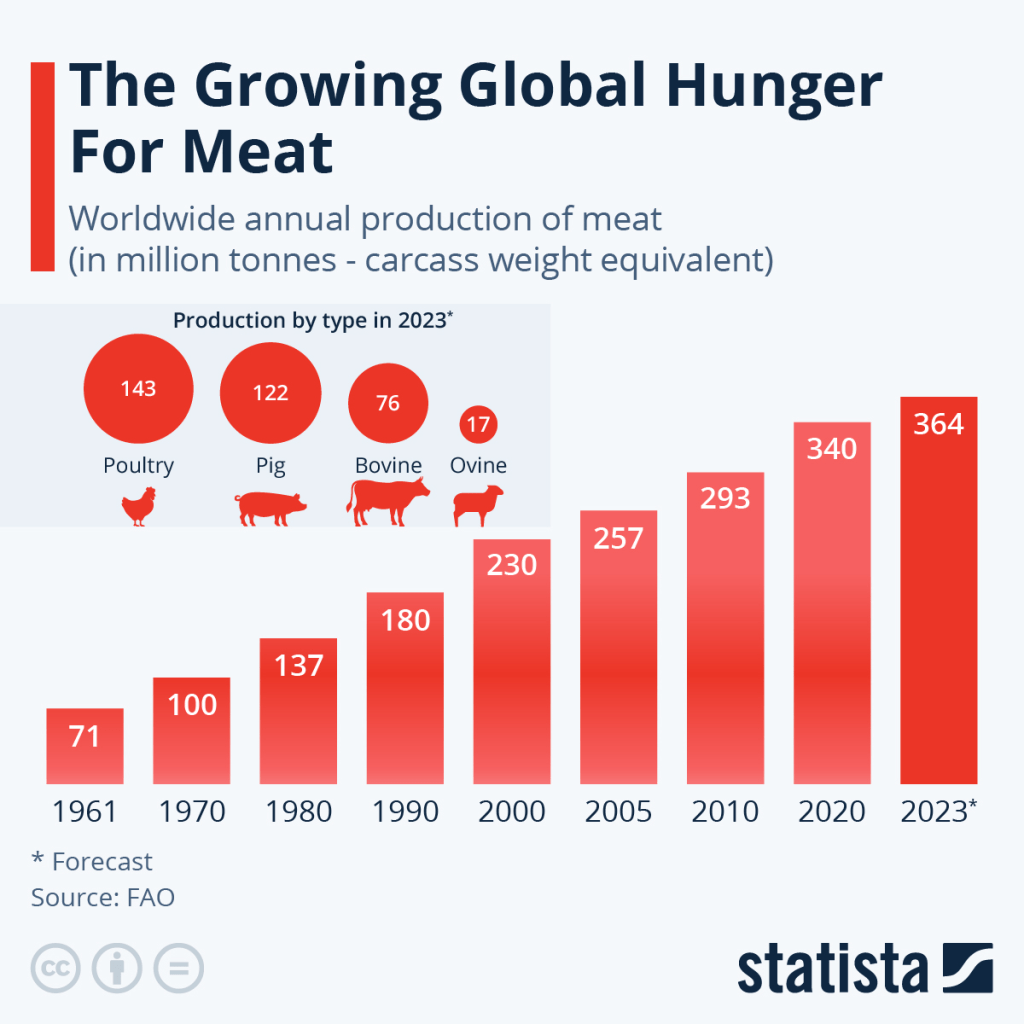

- in the Top 10 of world packaged food companies, 4 are meat producers (2 from Brasil);

- JBS, the world’s largest food company, is extending its protein reach from meat and fish into eggs buying the largest egg company in South America and acquiring a Top 10 USA-based egg company. There must be something in the water in Brasil, fellow Brazilian Global Eggs is on a buying spree in Europe and USA, too;

- the Top 10 global dairy companies each have revenues well above $10bn. and are hot foot to mop up smaller fry. Greedy? Maybe but you need annual sales above $500m. to capture scale economies;

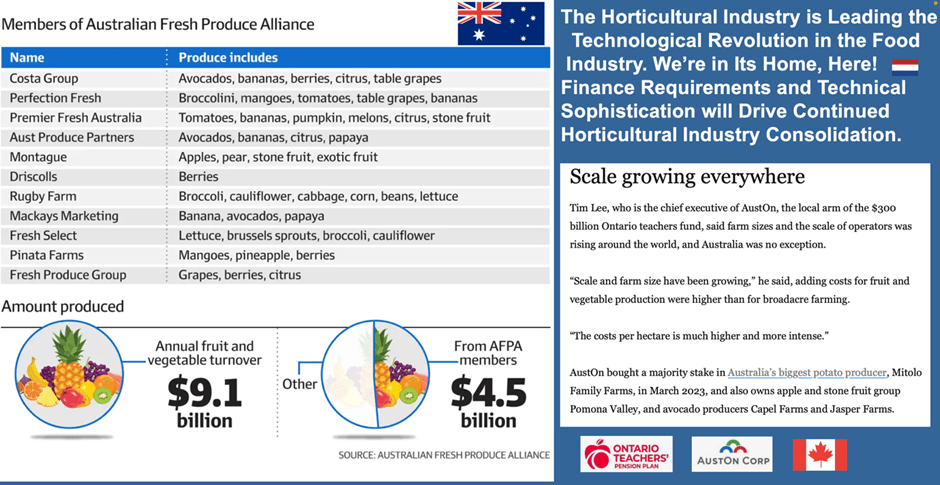

- horticulture has seen extraordinary global growth of big players – Driscoll’s in fresh berries, US-based Taylor Farms acquiring salad businesses in Europe, Shropshire’s and partners expanding;

- Norwegian-based Mowi is the UK’s largest salmon exporter and, in addition to Scotland, is farming salmon in Norway, Ireland, Canada and Chile to give it a 20% global market share.

The stark reality is that the investment cost to continue at the leading edge of commercial food production is accelerating through this decade which is driving farm business consolidation (it’s been a trend for donkey’s years). Larger-scale agribusinesses and processors seek larger-scale primary suppliers. Small farm businesses can be efficient but, invariably, they require scale to be profitable. In history, UK farmers have shown reticence in collaborating to gain scale with farm partners. Smaller producers need to be “under the wing” of a larger business to gain access to volume markets unless they have the skills and experience to develop local niche markets. DEFRA analysis indicates that “the average farm all too frequently loses money on its agricultural activities”. Most farms gain income from diversification activities such as letting buildings, solar energy, tourism. In history, the Basic Payment Scheme subsidy was financially key whereas now, there’s reliance on less predictable “green operations” payments. Looking through the remainder of this decade, the pragmatist should place more weight on private diversification income than on public environmental payments. Domestic food production, care of nature, the ecosystem, and the rural environment are vital, but they won’t have the political clout associated with national health and defence spending.

The Cup of Coffee Version

Global food prices may have eased slightly, but they remain far higher than pre‑Covid levels, squeezing consumers while farmers face rising input costs, volatile trade conditions and extreme climate events. Food security has climbed the political agenda, fuelled by concern over reliance on a narrow group of exporting countries for key commodities such as coffee, cocoa, sugar and oils.

UK food self‑sufficiency currently sits at around 60%. Historically it has fluctuated: below 50% pre‑WW2, peaking above 75% in the 1980s, before drifting down again. Improving farming profitability and food security is now firmly back in focus. One route, recommended by Minette Batters in her “Farming Profitability Review” (December 2025) is to “grow, make and sell more from our farms by strengthening the British food and drink brand at home and abroad”.

Different commodities tell different stories. The UK excels at growing grass, yet has not become a major exporter of dairy or red meat, despite strong domestic production. Poultry is a success story, though imports are ever present in processed formats such as nuggets and kebabs. Sugar and oilseed rape face pesticide constraints. Potatoes and pork are largely consumed in processed forms, with neighbouring countries’ products strongly placed in our market. Cereals remain relatively strong, though yields and returns are increasingly volatile. Fruit and vegetables remain the weakest area of self‑sufficiency, but perhaps with advantages in prospect from climate change.

At home, British consumers trust farmers and feel positively about UK agriculture, particularly younger generations. However, they also enjoy imported food and international cuisines, which now dominate ready meals and food service. The UK ready‑meals market is larger than total retail sales of fresh red meat cuts, reflecting a long‑term shift from ingredients to prepared foods.

Convenience has become paramount, especially for Gen Z, where “convenient” means immediate. As processors increasingly sit between farmer and consumer, provenance often fades from view unless the product is positioned as special or premium. International cuisine trends, amplified by social media, continue to shape demand. Korean food, Japanese‑inspired snacks and viral trends illustrate how quickly tastes can change. These forces are global and unlikely to reverse.

British consumers benefit from some of the lowest food prices in Western Europe, yet living costs are high and half of households are financially stretched. Price matters, but it is not the only driver. Fruit purchasing patterns show that consumers will pay more for perceived value, as seen in the rapid growth of berries despite higher prices.

If domestic production is to grow, British food must be “de‑commoditised”. Storytelling, provenance and standards matter. For more special meals, consumers seek food with adjectives that have redolence! Communicating value — not just price — is essential, alongside ensuring imported foods meet equivalent standards so domestic producers compete on fair terms.

Export growth will focus on premium markets, particularly the EU, which remains our closest and most important trading partner. Beyond Europe, opportunities exist in the USA and high‑income Asian markets, especially for products such as cheese. However, the UK will not compete on low‑cost bulk commodities against global giants.

The global food industry is consolidating rapidly. Large agribusinesses and processors increasingly dominate, driving scale requirements throughout supply chains. Investment costs continue to rise, pushing farm consolidation. Smaller farms can be efficient but often need collaboration, niche markets or alignment with larger players to remain profitable. Public support is becoming less predictable, and diversification income is increasingly important. While food production and environmental stewardship are vital, long‑term resilience will depend on commercial viability. Expanding UK food production is possible, but it will require realism, scale, collaboration and a stronger value proposition for British food — at home and abroad.